After more than a decade as a fashion designer, Dana Cohen was disillusioned. Excessive waste was rampant in every part of the industry – from surplus samples, to manufacturing scraps, to retail stores with “a disheveled mountain of garments that nobody wanted”, she said. “I was like, ‘I just don’t want to be a part of it any more.’”

Then Cohen, who had designed for brands including Banana Republic, Club Monaco and J Crew, had a chance encounter with a manufacturer that changed her course. Drishti Lifestyle, based in India, had a container full of leather scraps it didn’t want to discard. Together they experimented, and made some wallets and a handbag, all of which sold out. That was the very start of Cohen’s sustainable leather accessories company – and her mission to make a dent in the industry’s immense waste problem.

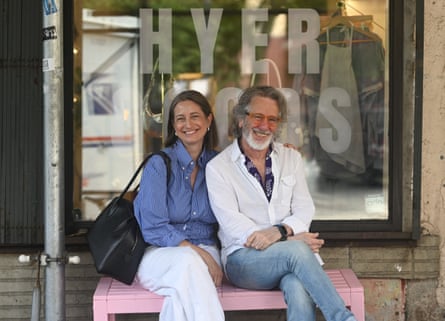

Launched in November 2019, Hyer Goods sells bags, wallets and other accessories made entirely from deadstocks: leftover scraps that would otherwise end up in landfills. Specifically, it uses luxury leather leftovers, retrieved from designer heavyweights like Hermes, Chanel, and Valentino. Deadstocks are sourced both directly from Italian factories – such as a tannery in the outskirts of Naples, Russo di Casandrino – and via “people on the ground” in Italy who have longstanding relationships with those brands.

The scraps are then transported to family-run factories in Italy’s Marche region, on the Adriatic coast: a mother-daughter-run factory produces the bags, and down the road, a father-son-run-factory assembles the wallets. “We literally load the scraps from the bags in a little car and drive it to the wallet factory,” Cohen said.

Designer brands typically only use the very highest grades of leather, so Hyer takes the “off-cuts” that are still above par, but may have blemishes like tick bites or stretch marks, and cuts around them.

Given the reliance on whatever is available, the Hyer collection is inherently small-batch, and a single line of bags might comprise a mix of different leathers. “We have never made 500 pieces of anything,” Cohen said.

The unpredictable supply can be hard. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” Cohen said. But she estimates this model has kept approximately 7,000 pounds of leather in circulation – and out of landfills – over the last six years of operation.

It’s a start in healing an industry that sends some 92m tonnes of textiles to landfills every year, producing between 4% and 8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“I appreciate any company that’s really trying to work towards the circular economy,” said Ann Cantrell, associate professor of fashion business management at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), “which is trying to keep things in the loop as long as we can and not go to landfill.” She said Hyer Goods’s model follows the “triple bottom line”: operating not only for profitability, but also for improving conditions for people and for the planet. If more businesses operate with such models, they can “continue to challenge the status quo” around issues like the overuse of virgin materials, she said.

Leather is particularly troublesome for its connection to cattle ranching, which is linked to deforestation, mass water use, and the emission of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Tanning also uses toxic chemicals that can contaminate waterways. On the other hand, leather is an extremely durable product, sometimes lasting decades. “So from that perspective, it is a sustainable material,” said Cantrell.

Sustainability is nuanced. “There’s no perfectly sustainable material,” said Elizabeth Cline, an author and expert on fast fashion and sustainability. But Cline said repurposing genuine leather is better than producing so-called vegan leather, or faux leather, which is made of plastics, even when it also contains some plant-based materials like cork or apple peels. “You’re eliminating the animal welfare issue, but creating new environmental problems,” she said.

The reality is that high-end consumers are still buying genuine leather. While Hyer’s average customer is the sustainable-minded person looking for greener alternatives, Cohen said she is starting to see more luxury-driven customers.

Hyer’s bestselling Ring Bag, made from lambskin Nappa, a premium leather known for its softness, typically sells for $465 – nothing to sneeze at but still a far cry from luxury brands that retail for several thousand dollars.

Cohen launched Hyer Goods just months before the pandemic. People weren’t buying fancy handbags during lockdowns so she briefly pivoted to sewing masks with leftover fabrics – even curtains – that she crowdsourced on social media. Consulting followers for opinions has continued to be a strategy. “I think people really like being a part of the process,” she says. “Not only is it a great way to connect with community, but it’s a really good way to make smart decisions.”

Soon, the bags gained the attention of influential figures like Katie Couric and internet chef Alison Roman. When Roman recommended the bags to her followers: “That was one of the best days for us, ever,” Cohen said.

Major brands like Bloomingdales, Nordstrom and Madewell now sell Hyer Goods bags, and in 2024, Cohen opened a brick-and-mortar store in New York’s West Village after winning a grant from the nonprofit ChaShaMa, which supports women and minority artists by providing them with subsidized real estate spaces.

Beginning April, the Trump administration imposed 10% tariffs on goods from Italy, leaving Cohen little choice but to raise prices. The price bumps initially led to a “huge dip” in sales, she said. Volumes seem back to normal now, though that’s hard to parse out due to seasonal shifts. “I’m not sure if the customer has gotten used to it, but I certainly haven’t,” she said. (In July, Trump announced additional tariffs on European goods, which European trade officials said would make continuing US-EU trade ““almost impossible”.)

Cohen said she has no plans to move operations to the US; many factories that she had considered weren’t capable of details like edge painting (to protect leather edges from fraying), which would sacrifice quality. “The craftsmanship that you can get in Italy just doesn’t compare,” she said. “‘Made in USA was just not an option.”

Cohen, who has five part-time employees, said she’d like to expand products into belts and shoes, start sourcing deadstock Italian cottons, and open a second store, perhaps in Brooklyn. She’d like to be fully circular, including hardware like zippers, which are not made from scraps.

But economic volatility – and simply the nature of a bootstrapped business that depends on a fluctuating supply – have delayed some of those plans. “Any dreams I had, I’ve put on hold,” she said. “Right now it’s just: how can we stay afloat?”

But nothing has changed her mission, which comes before any growth ambitions, she said. “My goal was never to be a behemoth organization,” Cohen said. “I just want to have a nice, small business for people who care.”

4 months ago

64

4 months ago

64

English (US) ·

English (US) ·